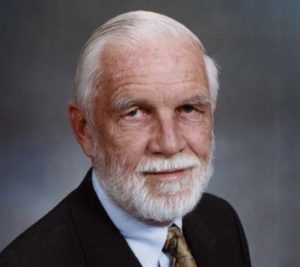

Our own Prof. Lee Langston helped Apollo 11 make history by being part pf the team designing the fuel cells that powered Apollo 11 to the moon and the return trip to Earth.

Our own Prof. Lee Langston helped Apollo 11 make history by being part pf the team designing the fuel cells that powered Apollo 11 to the moon and the return trip to Earth.

Read more in the Hartford Courant’s article.

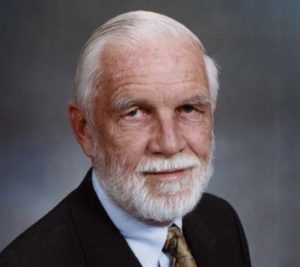

Our own Prof. Lee Langston helped Apollo 11 make history by being part pf the team designing the fuel cells that powered Apollo 11 to the moon and the return trip to Earth.

Our own Prof. Lee Langston helped Apollo 11 make history by being part pf the team designing the fuel cells that powered Apollo 11 to the moon and the return trip to Earth.

Read more in the Hartford Courant’s article.

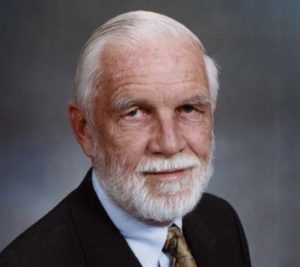

Our own Prof. Lee Langston helped Apollo 11 make history by being part pf the team designing the fuel cells that powered Apollo 11 to the moon and the return trip to Earth.

Our own Prof. Lee Langston helped Apollo 11 make history by being part pf the team designing the fuel cells that powered Apollo 11 to the moon and the return trip to Earth.

Read more in the Hartford Courant’s article.

The power you feel underneath you when you’re on a plane as it takes off is tremendous. The physics that enable the remarkable feat of lifting a 175,000-pound midsize commercial aircraft into the sky and keeping it there are just as incredible – and complicated.

There are four components to a commercial aircraft gas turbine engine: the fan that produces most of the thrust, the compressor, which compresses the incoming air, the combustor which burns the fuel to create high-energy gas, and the turbine that produces work from that gas to power the fan and exhaust to produce additional thrust.

The challenge in this system is keeping the flame in the combustor burning. Flame blowoff can occur when the air flow speed is very high, or the fuel-air mixture is weak so that the flame cannot be stabilized, so it moves downstream and eventually extinguishes itself.

University of Connecticut professor of mechanical engineering, Baki Cetegen has received $320,000 from the National Science Foundation to study this problem by investigating how different fuels and high levels of flow turbulence affect the occurrence of flame blowoff.